A few months ago, we were lucky enough to have agile guru Jeff Patton speak at our Open Charity meetup. We’ve written up an overview of his talk, including some tips that digital teams in charities might find helpful.

Agile has fixed a lot of problems in software development and the fast-paced, iterative approach enables organisations to deliver more software more predictably than ever before. We’re starting to see common agile practice around methods like Scrum, but Jeff warned that if you’re doing it strictly by the book, you might end up with something worse than if you weren’t using it at all. There is a danger in conflating agile practices with product development practices and losing sight of how some core differences between them could risk product quality.

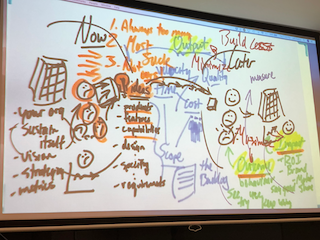

Jeff reckons the agile community urgently needs to fix the way it talks about product owners and product development. Here are his top five tips:

-

Stop treating the product owner like a customer

Organisations are often used to operating under a client-vendor model. It’s the client’s job to know their ‘requirements’ (what they want) and explain it. It’s the vendor’s job to listen, understand and figure out how they’re going to give it to you, how long it takes and how much it’ll cost, then give the client an estimate. After some negotiation, they agree an order. The vendor then does the work and delivers it. Everyone is happy.

But this doesn’t work so well within an organisation. If one side is put under too much pressure, the quality of the overall output is lost. This is a problem in by-the-book Scrum, where for ‘client’, read ‘product owner’ and for ‘vendor’ read ‘the team’.

A successful product is

1. Valuable to your organisation

2. Usable, and

3. Feasible to build given the time and tools available.

A product manager therefore needs to understand the organisation’s vision and strategy to assess value, to have an idea about user behaviour to assess usability, and to understand scale, security and performance to assess feasibility. Digital products age in dog years, after all (i.e. very quickly) - if you want to build something that lasts, you need to think about what’s coming, not what’s current.

This is pretty tough for one person to keep on top of, especially in a charity where you may also be juggling multiple other responsibilities! Product development should be a team sport and Jeff recommends that those responsible for the product surround themselves with a core cross-functional team of UX specialists, engineers and architects. These people collaboratively should be the decision-making body, each bringing their unique expertise to the table.

For charities, these roles will often be outsourced to an agency or tech partner, but it’s important that product decisions are still made collectively with the input of each domain expert.

2. It’s not about how fast or how much you deliver

Most product design projects start with ideas: products, features, capabilities, design, spec. The common time-cost-scope dependency says that you can only fix two of those things (or if you fix all three the quality will suffer). E.g. Fix the budget and the list of features, but allow it to take as long as is needed, or ring-fence a specific timeframe and budget and see how many features can be completed, or get a lot done in a short space of time but be prepared to pay a premium.

This helps manage the process but doesn’t factor in the views and behaviours of your users. We need to measure how people’s behaviour has changed as our outcome - do people use, keep using and refer your product to others? Plan to measure outcomes. Don’t have a feature that can’t be measured.

Jeff noted that the terms ‘output’, ‘outcome’ and ‘impact’ have been stolen from the nonprofit world and are now being used in business contexts for their valuable precision! Nonprofits need to demonstrate outcomes - not merely outputs - to help sustain themselves. This takes vision, strategy and metrics. Impact means people are happy because the organisation can sustain itself.

The problem with ideas is that everyone has them, so there are always too many. 60% of features in products fall into the ‘never used’ category because most ideas are rubbish. The job of a product manager isn’t to build everything you’re asked to, it’s to build less. Minimise your output while maximising - and measuring - your outcome and impact.

3. Don’t assume you’re building something worthwhile

The problem with the user story format of ‘X wants, so that..’ is that it doesn’t capture what the organisation itself needs.

In lean startup methodology, we have hypothesis statements. It distills the problem to be solved, the solution, the customer outcome and the business impact. You can think of hypotheses as bets. How confident are you that a thing is correct? The more confident you are, the lower the risk should be. But viewed as a bet, you see how much higher the stakes are for those more confident hypotheses.

Alongside your hypotheses, have a learning backlog full of risks, assumptions and questions. Prioritise them in order of what’s riskiest, then create a quick, cheap way to test it. You might have come across the concept of a ‘minimum viable product’ or MVP, but perhaps an even better acronym is a RAT - a ‘riskiest assumption test’.

When you put your product in front of people you collect data on how they use it and then refine/validate your hypothesis. The goal isn’t to build faster but to learn faster. Make small bets so you can quickly iterate through the build>measure>learn cycle.

There are plenty of super cheap ways to quickly test hypotheses and assumptions - interviews, paper prototypes, maybe a digital prototype. Something that you can put in front of a small subset of early adopters to test. Scale your learning investment (the resources you’re dedicating to test your hypotheses) with your confidence.

Agile development understands the build>measure>learn cycle but because it sprang out of the client:vendor pattern rather than internal process it’s easy to make the outcome and impact someone else’s problem. Watch out for this!

4. Stop spending so much time in the office

Hang out with your customers/users to fully understand them in context. You’ll learn a lot. Sit with them while they work and get them to show you their challenges. Everyone needs to spend face-to-face time with users to build empathy and insight, and charities that skip the user research phase of digital projects do so at their peril.

Even organisations that have a strong understanding of the general problem areas their users face often have only a very limited understanding of how individual users think, feel and behave in that context: their habits, preferences, hopes, ambitions. Without an understanding of these, your product is unlikely to fully meet their needs.

User research can pay dividends in the insight it gives everyone on the team into your service users and their challenges. Nor does it have to be hugely time-consuming - but make sure you follow a few key steps to mitigate bias and assumptions, otherwise your results may be invalidated.

In order to build a successful product in a charity, you need to satisfy both user value (creating something people actively choose to use) and social value (solving social problems). This is hard because these two may often be in tension - for example the habits and behaviours you observe may be the very things where your charity is aiming to influence a change! Eating healthily, doing regular exercise, managing finances etc. may be the outcomes your product is aiming to achieve, but you will probably need a different set of design tactics/features to incentivise people to actually use the product in the first place in order to achieve those outcomes.

5. Stop hiding work from the team

Follow the iterative build>measure>learn cycles through your Discovery phase and only once your idea has been validated (i.e. tested well against the metrics you chose), can it be taken forward to a main build.

Throughout this phase, share learnings through visual, collaborative artefacts like personas and journey maps. Most importantly, bring all members of the team into the design process so that everyone can contribute.

Good agile teams will discuss how they can engage colleagues and stakeholders from their wider organisation at the beginning of each ‘sprint’ of work. This could be regular (but lightweight) presentations, engaging a range of people in user research, or displaying your work and progress in a clearly visible spot on a wall where everyone can see. Different tactics will be more effective/appropriate for different audiences at each stage of the process.

Engaging as many people you can as early as possible will also help secure buy-in and excitement for your work. This is a huge advantage, as sometimes digital development work in a charity can be a lonely business, and having emotional as well as practical support from your team can make all the difference to your energy and motivation to see it through.

- Log in to post comments